“Chance favors a prepared mind."

-The bad guy in Under Siege 2: Dark Territory

“It’s not felony kidnapping so long as we get him to sign the release form.”

-Unnamed Pepsi Lawyer

Prep is everything.

I sincerely believe that prep is the single most important part of the filmmaking process. That belief was born out of lived experience, both in times where a detailed prep has totally saved my ass, and in times when I was not prepared enough and could feel the shame resonating through my body like magnetic waves in an MRI machine.

Today I’m going to talk about two projects, both of them heavily reliant on prep, but manifesting in very different ways. The first is one of my earliest projects, where prep was used to maintain an illusion for the audience. The second is one where prep became a necessity in order to avoid likely jail time and pull off something completely insane. The lessons I learned on that job influenced the rest of my career, and it’s why today I’m often told I’m the most prepared director people have ever worked with.

Part 1 - My first ad.

In 2013 I was a young, extremely green 30 year old director who was just beginning to dip my tow into the world of advertising. My first tv show, Key & Peele, had just debuted, and I was starting to get interest in commercial work through my agency at the time, Gifted Youth, which was the advertising arm of Funny Or Die.

Eventually I was approached by Pepsi Next with an interesting challenge. Write, produce, and finish a polished one minute spot making fun of Coca-Cola’s superbowl campaign. That wasn’t the challenging part. The challenge was that Coke would reveal their superbowl campaign a week before the big game, which meant that we’d have an insanely compressed timeline with which to do our thing. Pepsi wanted the finished spot in time to release it online the weekend of the game, so as to undercut Coke’s momentum.

I’m not here to talk about what transpired on that particular job, but suffice to say it was a success with the company. We made an ad depicting the behind the scenes of Coke’s campaign, with the cast of their shoot (motorcycle outlaws, cowboys, and Vegas showgirls) all trying to get a Pepsi out of as vending machine on set. Barry Rosen and Lou Arbetter at Pepsi liked it so much that they tried to make it their primary ad to air during the Super Bowl, but CBS claimed the deadline for swaps had passed, so it was released online only.

Still, the move was successful, and I came out of the job with some new fans at Pepsi, who in just a couple weeks found another campaign for me to work on, this time starring the NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon.

Part 2 - Let's fake it.

The campaign, at that time called "Ahh Genius" was for Pepsi's zero calorie brand, Pepsi Max. The conceit was simple, to show Jeff Gordon keeping his racing skills up to par in various unexpected environments, such as a member of a roller derby derby, parking cars as a valet, and test-driving sports cars in disguise with hapless salesmen.

The creative was mildly half baked, but the car salesman idea sparked something in me. I wrote my treatment in a matter of hours, naively submitting it was a text document with no supporting imagery. What if, I asked, instead of a more typical “zero calorie cola in disguise” campaign, we did something a little more…dangerous. What if we made it a true hidden camera spot, depicting Jeff taking an unsuspecting car salesman out for a high-stakes joyride. Being a bit green to the whole advertising thing, I don’t think I really understood what I was asking Pepsi to do, but I quote from my treatment:

Too many times have I watched an ad that's supposed to be reality-based and rolled my eyes and said "those are clearly actors" or "there's no way they couldn't have noticed the huge Alexa filming them in that tiny room." What I want to do is make a spot that communicates the core message of "People who drink Pepsi Max are smart do cool shit to have fun. And hidden camera pranks are cool.”

Everything about the spot needs to feel rough around the edges, like Jeff called a couple buddies over to film a prank for his youtube channel. We never feel the influence of a big budget, or a huge coordinated effort by, say, a soda conglomerate and a large advertising agency. Everything should have a homemade charm to it. This is Jeff having a good old time pranking squares.

Yes, my pitch to the multibillion dollar international soda corporation was: let me made a real hidden camera prank with your superstar athlete spokesperson where he puts the life of himself and a hapless, unsuspecting innocent person at risk by driving a car incredibly unsafely on public roads. Of course, the lawyers said “no fucking way.” Okay, well then what if we simply faked it.

There had been simulated hidden camera advertising before, of course, with Pepsi Max themselves having previously found success with Kyrie Irving’s “Uncle Drew” character, but what always bothered me was just how obviously fake it all seemed. From the cheesy over the top actors, to the plainly unhidden cinema-quality cameras, it all smelled inauthentic and slick. This time, I insisted, it would be different.

We’d use consumer level cameras, cast from real people, and create an immersive environment where as much of the action as possible was captured in real time. No scripts. No storyboards. No bullshit. Barry and Lou loved the punk rock audacity of it, and away I went to North Carolina.

From that point on, every decision was guided by this principle of authenticity. Again, quoting from my own treatment:

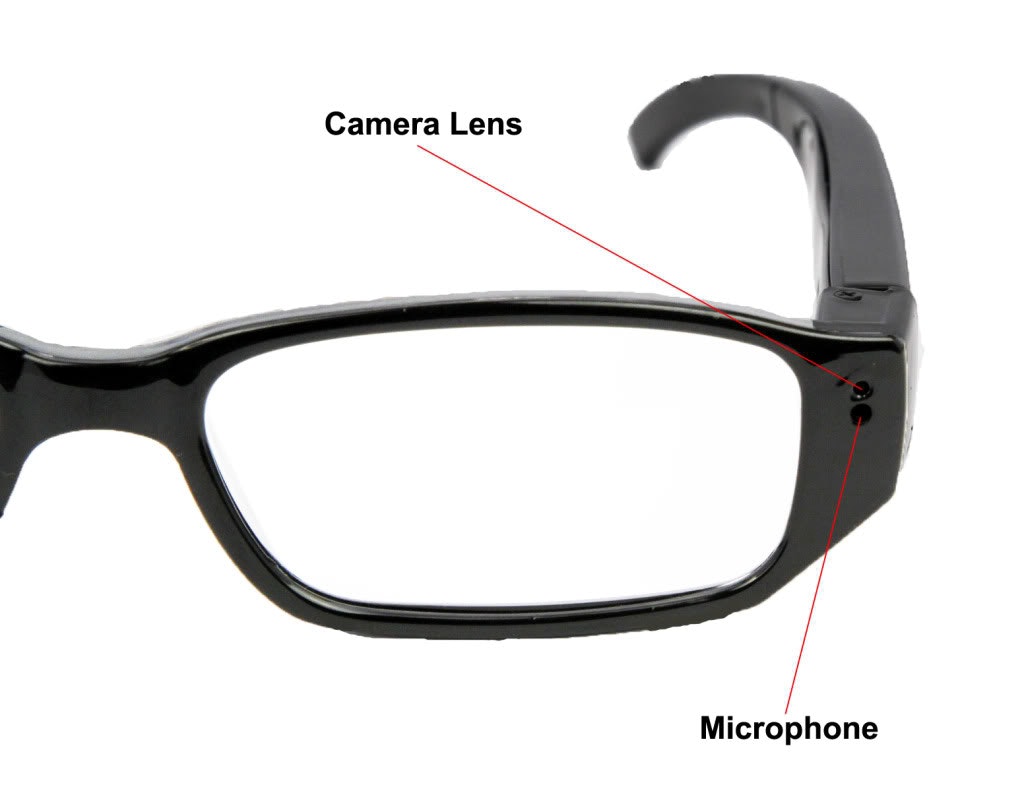

There's our hero camera, a decent quality HD camera, expensive enough to look good, but not a high-budget film-like monster with $60,000 lenses. That camera is for the process of Jeff going though makeup, and for getting long-lens voyeuristic shots when Jeff is in the field. Then there's two button cameras, one hidden in a can of Pepsi Max and one hidden in Gordon Jefferson's dorky dad-glasses, both of which Jeff carries with him to capture things our regular camera can't see. Those camera are grainy, possibly even black and white, akin to the kind of security footage you see from convenience store holdups. Then there's the GoPros stealthily mounted on the car itself, both to catch reactions and for some action coverage (we'll explain how those camera got there in the long version). Finally, I want to integrate some incidental footage into the cut. Is there an ATM security camera across the street from the dealership? Great, let's see the car doing donuts from that angle. Is there a teenager with an shooting iPhone skate videos with his buddies? Great, I want to see that footage too, even if it looks like we downloaded it from youtube.

I enlisted my brilliant DP from Key & Peele, Charles Papert, and mandated that we could capture no footage unless there was a reasonable explanation for where the camera had been hidden. As such, we purchased a spy pinhole cameras and fitted them places like Jeff’s eyeglasses and inside a real can of Pepsi Max. Shooting barely 360 lines of resolution, the grainy mush of pixels helped sell the reality of what we were doing. Our primary cameras were Panasonic VX-2000s, prosumer level cameras with fixed lenses that could easily be hidden from view, and our operators shot from inside vans with tinted windows for concealment. And finally, we relied on go-pros with simple mounts for most of our driving footage.

The one nod to standard advertising operating procedure was our storyboards, which I insisted were basically useless since we’d be capturing hours of raw material in order to shape the end narrative, and our shoot would therefore never be traditionally “board-focused.” The agency won in demanding their creation, however, and so I made sure they were the worst, least-helpful storyboards ever made.

Casting was similarly method. We hired from local community theater troupes to get as non-professional a performance as possible out of the people who would be featured on camera. Our salesman actor was told as little as possible, and on the shoot day simply worked amongst the real staff of the used car dealership location we found on the outskirts of Charlotte, North Carolina. Jeff was made up with a disguise, a character we called “Gordon Jefferson” with a backstory as an amiable middle-aged dad who wanted to test drive his mid-life crisis dream sports car. I mocked up these concept images for the pre-pro book:

On our first shoot day, we shot the disguise makeup process at our production office before doing a company move to the dealership we’d be using, Troutman Motors.

Once there, we ran immersive long takes, where Jeff would jump out of a van, talk to the salesman, wait for him to fetch the keys while Jeff’s team of “helpers” threw some mounted cameras onto the Camaro we selected. I fed lines to Jeff through an earwig, and while we did run traditional takes, we never broke the shoot down into specific setups, choosing to let the action play out as organically as possible. Each take ended when Jeff and the salesman entered the car to begin the test drive, making sure Jeff placed the can camera just so in the cupholder in order to capture the salesman’s reactions.

Of course, legally speaking, Jeff could not actually drive the car. He was limited to pulling it out of the parking place, doing a few lurching start and stops (to help sell the illusion that his character, Gordon Jefferson, was overwhelmed by the raw power of the Chevy Camaro’s V8 engine), and then that was a cut. Jeff was frustrated by these restrictions, and at one point took it upon himself to do some donuts in the parking lot before agreeing to stop the take. Naturally, those wound up in the edit.

Then we shot the ending, where our salesman character freaks out, threatens to call the police, and is only dissuaded by Jeff’s dramatic reveal as his true self, NASCAR champion and hero to the people of North Carolina. The salesman actor, Steve, did a marvelous job of selling the panic of someone who thinks they’ve just been taken on a joy ride by a madman. To be honest, the whole spot hinged on his ability to sell the reality, and he did an incredible job of it.

On day 2 we shot the driving, which was conducted off site, at a nearby decommissioned cigarette manufacturing plant, which offered plenty of winding roads that we could own a full lockup on. The driving was performed by Richard Petty Driving School instructor Brad Noffsinger, and Steve gamely sat in the passenger seat in view of our can cam and spent the whole day pretending to be terrified. Of course, Brad was driving plenty aggressively, so often the fear was quite real. We’d rehearse a stretch of road, set up cameras to simulate incidental footage like security cameras, and shoot. The weather sucked and we battles tech issues with image transmission to the client peoplemover, but we got it all.

Everyone seemed happy enough with the shoot, but looking back I think there were a lot of questions about how we were going to make all of the various pieces we’d shot — much of which was deeply crappy footage from low res cameras — work in a cohesive edit. Back in Los Angeles, I sat down with our editor, Doobie White at Therapy Post, and got to work.

We spent about three days whittling the material down to a long-form for online, then shaving even further to generate a couple different 30s that would air on tv during auto races to hopefully drive traffic to the long form. There wasn’t a lot of back and forth with Pepsi, at this point Barry and Lou had decided to cut the agency out of the process and give notes directly to us. Doobie had the brilliant idea in the eleventh hour to start the longform with a teaser flash forward to serve as a hook, and we were done.

Here now, is the finished long-form ad:

A few weeks later, the 30 debuted during a NASCAR race, and the long form went up on youtube, embedded on the Pepsi Max website. I knew we had something special on our hands when, about 12 hours after the video went live, I received an email from a friend in another state, sending me the video with the message “You have to see this, it’s fucking hilarious. By the end of the first weekend, we had 2.5 million social shares. After a week we have over 40 million views.

Most heartening of all was the sheer scale of just how many people we fooled. Everyone thought it was legit. You’d see comments like “How did Pepsi even okay this?” and “I feel bad for the poor salesman.” In a twist that we now recognize to be a terrifying harbinger of our current political climate encouraging reality-denying groupthink, lots of people claimed to know the salesman personally, or someone else who was there, and independently vouched for the authenticity of the spot.

The size of the reaction was overwhelming. Everyone at Pepsi was thrilled, of course, and Jeff enjoyed his sudden catapult back into the national conversation. But as the ad spread, people began to grow suspicious. That sparked a series of internet sleuths pointing out small inconsistencies in the footage, and those criticisms were spearheaded by one automotive journalist, named Travis Okulski. Here’s a representative clip from a popular network morning show, Good Morning America, who did a piece on Travis calling out the ad’s veracity:

By that point it didn’t really matter much. People loved the ad, were sharing it, and everyone was happy. I was annoyed that I hadn’t managed a perfect deception, but c’est la vie. Life went on, we all won a bunch of Clios and other Ad awards, and that was the end of the story.

Or so I thought.

Part 3 - The Sequel

One year after the first ad had gone up, I received a message from Pepsi. Would I be interested in making a sequel? And if so, what would I want it to be? Jeff was already onboard and was making one request: this time he wanted to actually drive. Apparently his ego had taken a bit of a beating when word got out that a stunt driver had done most of the actual on-road maneuvering. So, they asked, what did I think? Any ideas for what to do for a second test drive.

My answer was simple. The only way I was coming back was if we could do the prank for real. And not to just anyone, but to the one person who had been most vocal about the first Test Drive being completely fake. Travis Okulski.

To Pepsi’s eternal credit, Lou, Barry, and the rest of the brand marketing team immediately understood that this was the only way to up the ante. Lou promised he would do everything in his power to push it through. Working without an agency, we cooked up a plan. We’d work with his automotive website employer to create a fake reason to send him down to North Carolina.

Once there, he’d stay in a hotel, getting picked up and driven via taxi cab to a track to test drive the upcoming Corvette design refresh. However the cab would be driven by Jeff Gordon in disguise, in character as an ex-convict with a long rap sheet of prior offenses. We’d have a fake state trooper pull the cab over, threaten arrest, and then Jeff would panic and take off, prompting a high speed chase before a big reveal. It sounded ludicrous to imagine, but to our shock when we reached out to Travis’ company, they agreed to help us. One of Travis’ good friends agreed to be our man on the inside and help us get the personal information we needed to set Travis up.

Things moved very quickly. Pepsi’s internal legal counsel was of course horrified and had all manner of reasonable rejections. But Lou, true to his word, browbeat them in conference call after conference call until they relented. They drafted a thick document of releases that needed to be signed after the fact, prompting the memorable quote I shared at the beginning of this presentation.

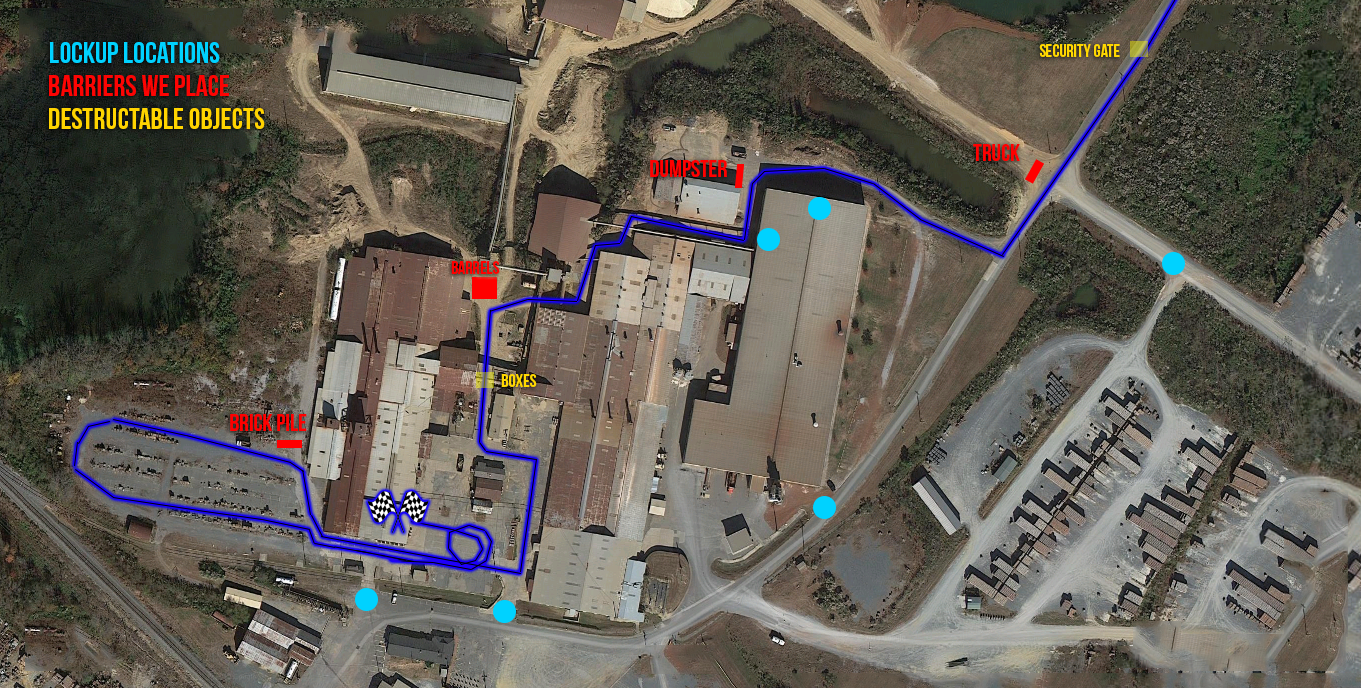

I flew to North Carolina to scout locations, settling on an abandoned brick factory that offered a diverse course for some intense stunt driving, easy access to the local highway, and a large central warehouse to serve as our control center and the setpiece for the final reveal. For the better part of two weeks we planned the course, custom outfitted a Chevy Caprice with high tech hidden cameras and transmission gear, and began to plan. As usual, I defaulted to meticulous prep, putting together overhead maps of the course, with camera plots for each section.

And as usual, I once again enlisted my photoshop skills to make a highly detailed mockup of what Jeff’s character would look like.

Planning a normal ad shoot is a huge task in and of itself, but factoring in committing multiple potential felonies and with a single take that can only occur only once in real time was, well, a fucking mind-melter. It was like planning a bank robbery and a kidnapping at the same time, but with the usual advertising scrambles like getting color correct copy and dealing with the talent’s time restrictions on set.

In order to ensure Travis’ safety, we reached out to his doctor, who mildly violated privacy laws by confirming that Travis did not have any heart conditions that could be aggravated in high stress situations. Indeed, Travis had partaken in high speed driving many times for his line of work, so surely he’d be no stranger to the spirited driving he was in for. A psychologist consultant told us that his flight or fight instincts were likely to kick in, so we devised ways of making sure the rear doors could be locked and the interior handles disabled. We also reinforced the plastic partition between the passenger and driver, in case Travis tried to stop Jeff by force.

We found a hotel nearby, calculated signal ranges for our audio transmitters in the trunk, and worked how to secure five separate HD recorders in the trunk of a car that needed to run for a long time and survive a car chase, with quad split backup. We rehearsed the route, timing the travel times involved and then rehearsing the driving on site ad naseum with stunt drivers.

We cast a local stunt driver as our state trooper policeman and manufactured fake badges and graphics for his cruiser. The course was designed to have a few dramatic obstacles to heighten the reality, such as an imposing chain blocking the entrance to the brickyard (also serving the double duty of stopping bogeys from entering our course accidentally on the day), some empty barrels for Jeff to dramatically run into, and several gravel skid tracks. Inside the end warehouse we set up lots of Pepsi Max branding and some confetti cannons.

Our minds raced with potential problems and how to solve them. What if the State Trooper vehicle got stuck behind traffic or caught at a red light? Where should it lie in wait in order to get behind them, but also far enough away from the entrance to the brickyard so as to let Jeff’s character properly panic? What if Travis recognized Jeff (he was, after all, a huge NASCAR fan)? And the worst possibility: what if Jeff crashed the car. What if Travis caught wind that something was amiss? What if his friend Ray double-crossed us? What if any one of a million things that could go wrong…did? Were we taking a stupid risk in the name of selling zero calorie cola? (Yes, we were)

As the shoot day approached, nerves were frayed. I don’t remember getting a lot of sleep the night before the shoot.

The plan was this: Travis would arrive at his hotel early in the morning, where he was told he’d need to be on call for his taxi pickup in the early afternoon. Jeff would arrive, and we would first let him rehearse driving the stunt course in order to learn it. After a couple hours of that, we’d put him through hair and makeup to get into character, after which we’d run a full dress rehearsal, with our stunt coordinator standing in for Travis. This would run as a full realtime dress rehearsal of all of the beats, including the hotel pickup.

Assuming the dress rehearsal went well, we’d reset and go for real.

On the day, Jeff was excited. He’d finally get to prove he could drive the ass off of a regular car and be the prankster he’d been pretending to be in Test Drive 1. It wasn’t until the dress rehearsal that the gravity of what we were doing hit him. But the dress exposed a problem: the hotel we’d chosen was too far away for our production walkie’s to work, and there was no way to receive audio signal from the car in our command center on site. The only option was to use a cell phone to stay in contact with Jeff and monitor the situation. Jeff wore a bluetooth headset, and for the first ten minutes of the run, it was our only way to keep tabs on their progress or for me to communicate with Jeff.

The dress rehearsal went well, but Jeff didn’t have to be fully in character. None of us knew how the athlete would fare under the pressure of being locked in the car with his unwitting victim, or how his driving might change when under pressure of the real thing.

It was finally time to do it. Jeff drove out to our staging area, were our camera crew rolled and slated the cameras, activating the onboard recorders. The sun had just come out, so we made some last minute exposure changes that ended up saving our ass. The emerging sun had other consequences, which I’ll get to in a moment. Travis was told to stand by for his taxi’s arrival, and Jeff pulled up to his hotel. At this point, Jeff was just a voice on the phone. I told him to remember the plan, stay in character, and that I would always be there to feed him lines or deal with issues that came up.

Travis came out and got into the backseat, thankfully not opting to put anything in the trunk (we’d dressed the equipment in as best we could, but it made the trunk abnormally compact). However, when he got in, he didn’t put his seatbelt on. Luckily, we’d rehearsed this. “Can you throw that seatbelt on for me?” Jeff intoned in the thick southern drawl we’d discussed for his character. Travis, as our psych profile suggested he would, obeyed the request.

As they made their way down the highway, a flurry of activity was taking place around them. We’d arranged for a tail car to keep an eye on their progress, constantly updating my AD team as they crossed intersections. Meanwhile, I monitored their polite small talk, feeding lines to Jeff from time to time so that we could drip out his character’s backstory. Travis mentioning he was from New York was the perfect opportunity for Jeff to mention that he had done some time with people from those parts. Later, when reviewing the footage, we’d laugh at Travis’ involuntary look of shock at this reveal.

Their journey to the brickyard was probably the longest ten minutes of my life. By the time I gave the signal for our stunt Trooper to pull out into traffic behind them, my hands were clammy with sweat. Lou and Barry stood near me in our command center, no one saying a word other than myself and my first AD. Right on cue, the Trooper’s lights went on behind them. Jeff notices them and begins to swear, cursing his luck. When they finally pulled into the brick factory road, the signal transmission kicked into life, and we finally had picture. The taxi crept to a stop. This was, we had discussed, our last opportunity to abort. Once Jeff pulled away, the case would be on, and there would be no stopping them, for better or for worse.

I’m going to take a moment to recognize someone without whom which this whole crazy adventure would not be possible. You don’t often think of professional athletes as good actors. Hell, usually most of your day is spent trying to coax one halfway decent line reading out of them. But goddamn if Jeff Gordon didn’t give the performance of his career. He was perfect. His rising panic perfectly fueled Travis’ own increasing anxiety, and when the moment happened, we got a reaction that we only dreamed of.

Rather than give any more away, here’s the commercial, so you can see the rest in practice for yourself:

Needless it went off without a hitch. When the confetti cannons went off and Jeff revealed himself to Travis, we were all delirious with relief.The moment I called cut, I ran up to Travis with a clipboard of the legal documents, introduced myself, and asked him to sign, which, thankfully, he did without even reading them. Jeff was particularly pumped, he kept whooping and hollering in joy. Later he told me that it was the closest he’s ever come to matching the feeling of winning a season championship, and it was his favorite advertising memory of his career.

As the confetti settled and reality began to take hold, I asked my DP if he had checked the footage. He gave me a grim look. All of the HD recorders had overheated, crammed together in the trunk in the afternoon sun. The data on all of them was incomplete and corrupt. The only recorder that had continued running without issue was the quad split backup. As such, our footage ended up being a quarter of the resolution we intended. The same aesthetic approach that had served us so well on Test Drive 1 would also be present on the sequel, albeit not by choice.

That night, many a drink at the Charlotte Mariott was raised to toast our success. Travis was invited, but he did not come.

The next day, we again covered the car chase, this time with stunt drivers in both cars, and a stunt double for Travis. This allowed us to get all of the external shots of the chase without needing to rent 25+ cameras. As in the original Test Drive, all of these shots were chosen as cameras that could have captured the chase in real time.

Back in LA, Doobie White and I once again dove into the footage. Ultimately, Pepsi only asked us to remove two moments. The first was part of Travis’ initial reaction to the chase beginning. It’s a cry of despair just desperate enough to tip the viewing experience from fun to harrowing, and it was a good call to lose it. The second was a moment where Jeff, fully engrossed in his character mid-chase, sees the police car attempting to block him in and shouts a loud “FUCK YOU!” while flipping the bird. It’s hilarious, but I can see how it made Pepsi a little too nervous in a spot where their star already spouts copious f-bombs.

Looking back, I still can’t believe they let me do it, and even though the reception was not quite as rapturous (20 million youtube views in comparison to the original’s 46 million), it’s still one of the proudest achievements of my career.

Both spots taught me the value of meticulous planning, even though the methodology for each of them ended up being quite unique. And though I’ve yet to kidnap another person (on film, anyways), I still plan every shoot like I’m running the risk of committing a few felonies if I don’t have my shit together.